A Legacy of Service

In 1949, Texas lawmakers were facing a phenomenal challenge. In the burgeoning postwar years, public schools were bursting at the seams. Facilities were inadequate and teachers were in short supply. School systems could not meet the demands without increased funding and a framework for support.

Something had to be done.

“Proposals for improving education in Texas must be based upon the needs of the state,” said a committee of leaders that had been tasked with finding solutions. “Personalities, petty quarrels, local self-interest, political alignments, selfishness — these must be forgotten by any group entrusted with designing a better education for Texans.”

That message, which still resonates today, was one of many that helped pass the Gilmer-Aikin laws, designed to usher in the framework for a modern public education system in Texas. The landmark legislation also laid the foundation later that year for the establishment of the Texas Association of School Boards.

In the 75 years since that pivotal moment, much has changed, for both the Lone Star State and TASB. Through it all, however, the Association has persistently focused on its purpose: to strengthen public education in Texas.

TASB's first convention, 1950. TASA | TASB Convention would begin in 1960. (TASB archives)

“Our mission has always been to provide outstanding training and support so that the voices of our board members are amplified, and they have the opportunity to ensure that every child has a quality education,” said TASB Executive Director Dan Troxell. “We do that through advocacy, through great training on governance, and all the services we provide.”

As TASB celebrates this major milestone, here’s a look at how it all came to be.

The Evolution of Public Education in Texas

The idea that public education was a public good took hold before statehood, when the founding fathers cited the Mexican government’s failure to establish a public school system among the reasons for their call for independence.

“Unless a people are educated and enlightened,” they stated in the Texas Declaration of Independence, “it is idle to expect the continuance of civil liberty, or the capacity for self-government.”

In the fledgling Republic of Texas, leaders continued their cry for a foundation of public education — but they lacked the resources to make it happen until after statehood in 1845. In January 1854, the Texas Legislature sold land to the U.S. government for $2 million and created the Permanent School Fund. With this, public schools took hold in the state.

Still, the ensuing decades presented constant challenges. Funding was needed for textbooks, facilities, and teachers. Coordination of the school system was difficult in a large, rural state. Issues surrounding segregation exacerbated the challenges.

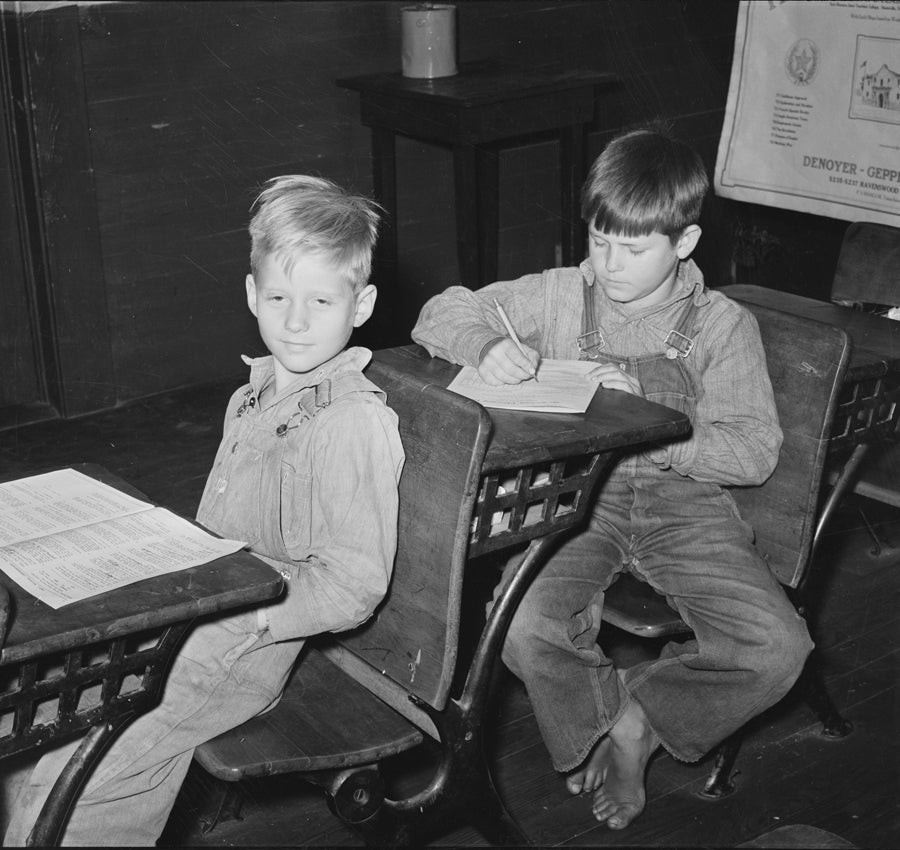

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, many children left school to help their parents make a living, and overall enrollment fell nationwide as the number of 5- to 13-year-olds declined.

Depression-era schoolchildren in San Augustine County (Library of Congress photo archives)

The situation prompted the State Board of Education in Texas to conduct a three-year study on the adequacy of Texas schools, and in 1938, the findings resulted in a bold proposal to consolidate school districts throughout the state. That plan wouldn’t be implemented until the Gilmer-Aikin reforms over a decade later, when more than 6,000 districts were regrouped into 2,200 units.

Like the Great Depression, World War II had a devastating and transformational effect on education in Texas. Resources were largely directed toward war efforts and away from social programs, including schools. Dropouts became common. High school enrollments across the country decreased from 6.7 million in 1941 to 5.5 million in 1944. Many teachers and students left the classroom to enlist.

But change was imminent. During the war, more than a million military personnel came to Texas for training, and many returned to make it their home.

Their overseas experience highlighted the importance of an educated populace in maintaining a strong democracy. War-related industry lured farmers and small-town residents, including women and minorities, into urban and suburban centers. With a net population growth of 33%, Texas quickly transitioned from mostly rural to increasingly urban. Also, the unprecedented postwar baby boom greatly affected school enrollment nationwide, which grew by more than 50% in the 1950s.

It was in this context that the push for reform gained momentum and resulted in the passage of the Gilmer-Aikin laws in 1949.

A Time for Unification

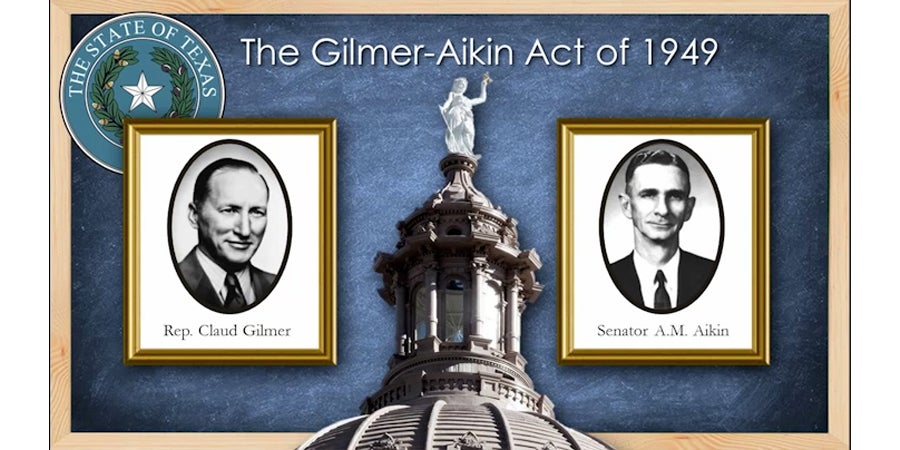

Two years before the new laws passed, the 50th Texas Legislature created a committee to study education reform. Rep. Claud Gilmer of Rocksprings and Sen. A.M. Aikin Jr. of Paris led statewide efforts to collect information from school leaders, elected officials, the press, and civic groups about needed changes. Input from such a wide swath of community leaders across the state was invaluable.

Rep. Claud Gilmer and Sen. A.M. Aikin Jr. (TASB archives)

After the laws were enacted, an implementation team under the state auditor held 32 regional meetings in summer 1949 to explain the changes to school superintendents and to notify each district of its state funding entitlement for the coming year. These regional meetings highlighted the need for more periodic meetings of school leaders and for neighboring school districts to work together in solving problems. A statewide association of school boards seemed like the perfect idea.

As it turns out, the idea actually had been planted years earlier.

In 1941, a small group of school trustees from the Gulf Coast area met with the goal of creating a statewide association. Their plans were tabled with the outbreak of World War II that year, but they kept the dream alive.

Ray K. Daily, TASB's first president (TASB archives)

After the war, they were ready to act. In November 1946, the Houston Board of Education hosted a small group of trustees interested in forming an association. Guiding the group were Ray K. Daily, a Houston school board member and leader of women’s groups in the Gulf Coast area, and J.W. Edgar, Austin school superintendent who would later serve as the first Texas commissioner of education. Over the next few years, other interested trustees joined the discussion, and in 1949, an expanded group met in Fort Worth following the Texas State Teachers Association Convention.

Soon afterward, a committee met in Austin and consulted with The University of Texas, which offered organizational and funding assistance as well as office space on campus. The full group gathered again in November 1949, this time with about 100 trustees representing 26 districts from across the state — and TASB was born. Its purpose was clarified by Daily, the organization’s first president.

“Every activity of the Texas Association of School Boards is aimed at the task of helping YOU do a better job for the children of your community,” she wrote in a letter to all school boards in Texas.

Willie Kocurek, TASB's second president (TASB archives)

Texas school trustees, who served growing metropolitan cities, small towns, and isolated, rural areas, finally had a way to connect with each other and collectively forge a positive future for Texas schools. As Willie Kocurek said, after becoming TASB’s second president the next year, “School board members had no power, nor did we have a unified voice to act as an organization. Only by banding together as an association could we be effective. There would be strength in numbers.”

One Mission in Mind

In the last 75 years, TASB services have morphed and expanded to help school boards and the districts they serve overcome challenges and be proactive. But the organization’s core purpose has never changed.

“I think what has sustained us is that our members have a calling to serve their boards, their communities, and the children who are being educated in those communities. I hear that from board member after board member, and that’s what fuels my passion at TASB because we’re serving people who are serving others,” said Troxell. “Our mission — and theirs — has never wavered.”

James B. Crow, who served as executive director from 1995 to 2021, expressed the same sentiment during TASB’s 50th anniversary in 1999: “Although much has changed over the last half century, our mission has remained fundamentally the same: to promote educational excellence for Texas schoolchildren through advocacy, visionary leadership, and high-quality services to school districts.”

The theme has remained constant since the very beginning. As a founding member, Kocurek reflected on TASB’s journey in 1999: “This Association is such a great, great enterprise. It has expanded into areas of service and creative education that few would have dreamed of 50 years ago. But the mission of service is still the same. What is most pleasing to me is that the germ that was planted so long ago has grown as we’d hoped — and beyond.”

This article first appeared in the Jan/Feb 2024 issue of Texas Lone Star.

TASB History — How It All Began

TASB has been working on behalf of Texas public schools since 1949. We provide innovative solutions and services to help lessen the burden of government.

Melissa Locke Roberts

Melissa Locke Roberts is a staff writer for Texas Lone Star.